You cannot understand the birth of the computer without first understanding a paradox, a collision of two worlds embodied in the mind of one woman. To find the source code of our modern world, you have to go back to 19th-century London, to the story of a child born of a volatile union between the two great forces of the age: poetry and mathematics.

Her father was Lord Byron, the brilliant, brooding poet—a man whose life was a testament to romantic excess, a figure "mad, bad, and dangerous to know."¹ Her mother was Anne Isabella Milbanke, a woman of sharp intellect, a gifted mathematician whom Byron himself nicknamed the "Princess of Parallelograms." Their marriage was a brief, spectacular disaster. Fearing the "Byronic madness" she saw in her husband, Lady Byron left him just a month after their daughter, Augusta Ada, was born. She was determined to save the child from the father's perceived insanity, and she had a unique tool in mind for the task: a strict, unforgiving curriculum of logic and mathematics. She believed the cold, hard certainty of numbers could extinguish the dangerous, flickering flame of poetry she feared Ada had inherited.

But she didn't extinguish the flame. She fused it to the engine of logic. In trying to suppress the poet, she accidentally created a prophet. Ada Lovelace would grow up to call her approach "poetical science,"² a unique ability to see the beauty in a logical system, the artistry in an algorithm. And it was this vision that allowed her to ask a question no one else was asking. In an age of steam engines and mechanical calculators, she looked at a machine designed to crunch numbers and saw a future where it might do almost anything else. What if, she wondered, a machine could manipulate not just numbers, but symbols? What if it could compose music? What if it could weave patterns of logic as intricate as any tapestry?

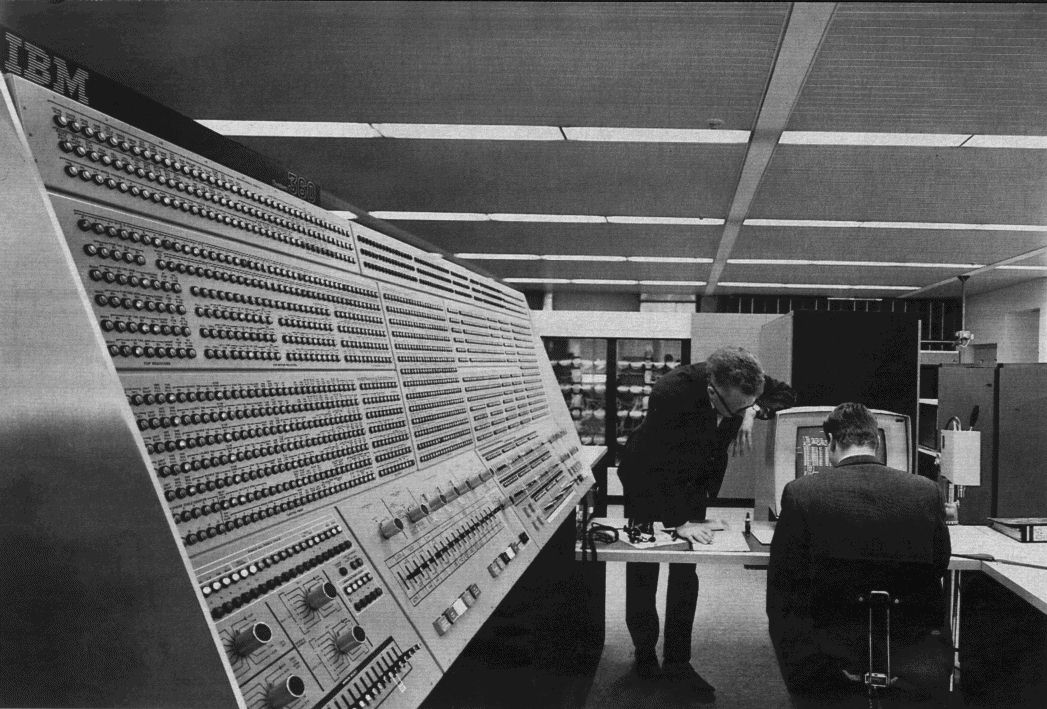

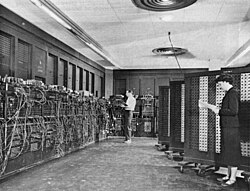

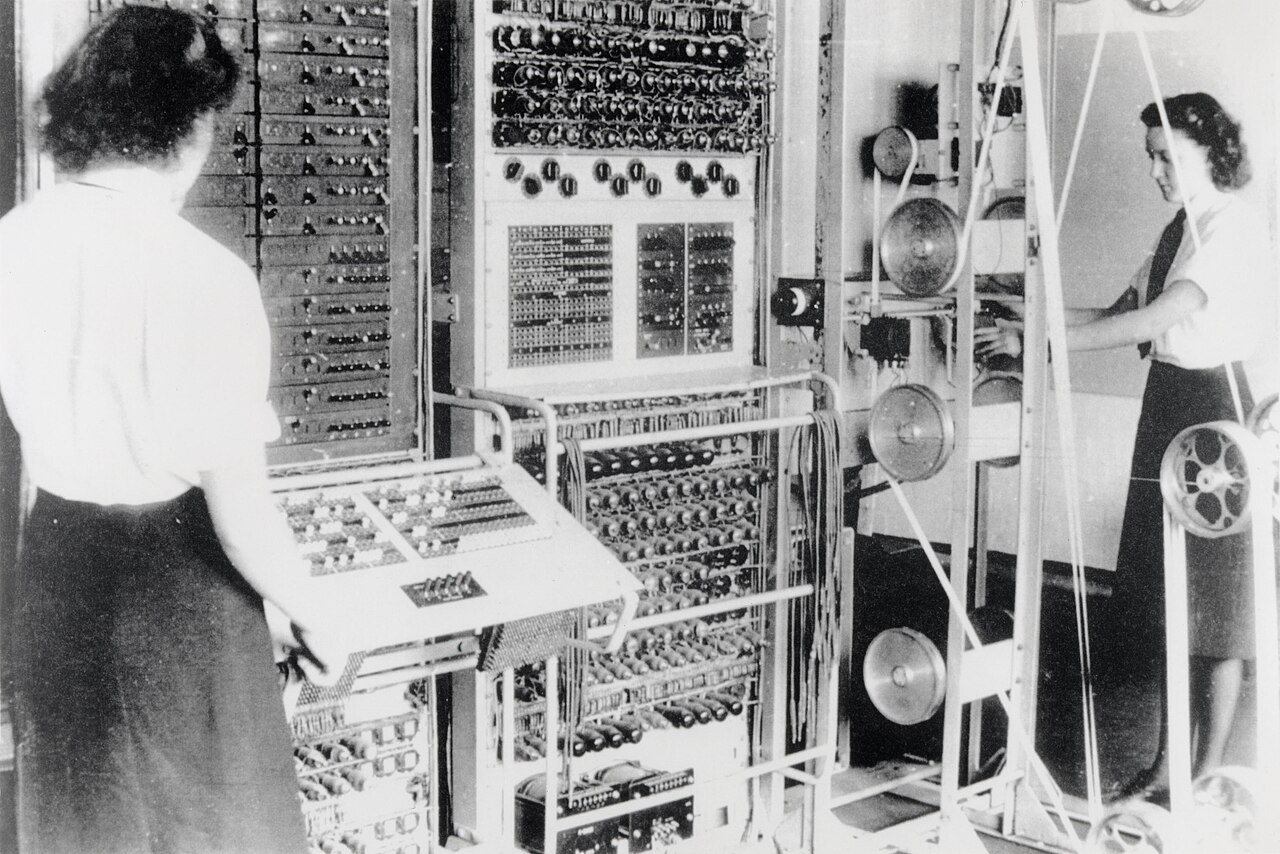

The machine that sparked this vision was the brainchild of the brilliant, irascible inventor Charles Babbage. When a teenage Ada met Babbage in 1833, she found her intellectual soulmate. Babbage was consumed by a grand obsession: the Analytical Engine. It was a breathtakingly ambitious design, a sprawling dream of brass gears and iron levers that was, for all intents and purposes, the blueprint for a mechanical, general-purpose computer. It had a "store" for holding numbers (memory) and a "mill" for processing them (a CPU), all controlled by a sequence of instructions fed into it on punched cards.³

Babbage saw it as the ultimate calculator, a device to eliminate human error from astronomical and mathematical tables. But Lovelace, with her poetical science, saw something more. In 1842, she was asked to translate an Italian engineer's paper on the Analytical Engine. She took the task and transformed it. Her translation became a canvas for her own ideas, and the "Notes" she appended were nearly three times longer than the original article. It is here, in "Note G," that she etches her name into history.

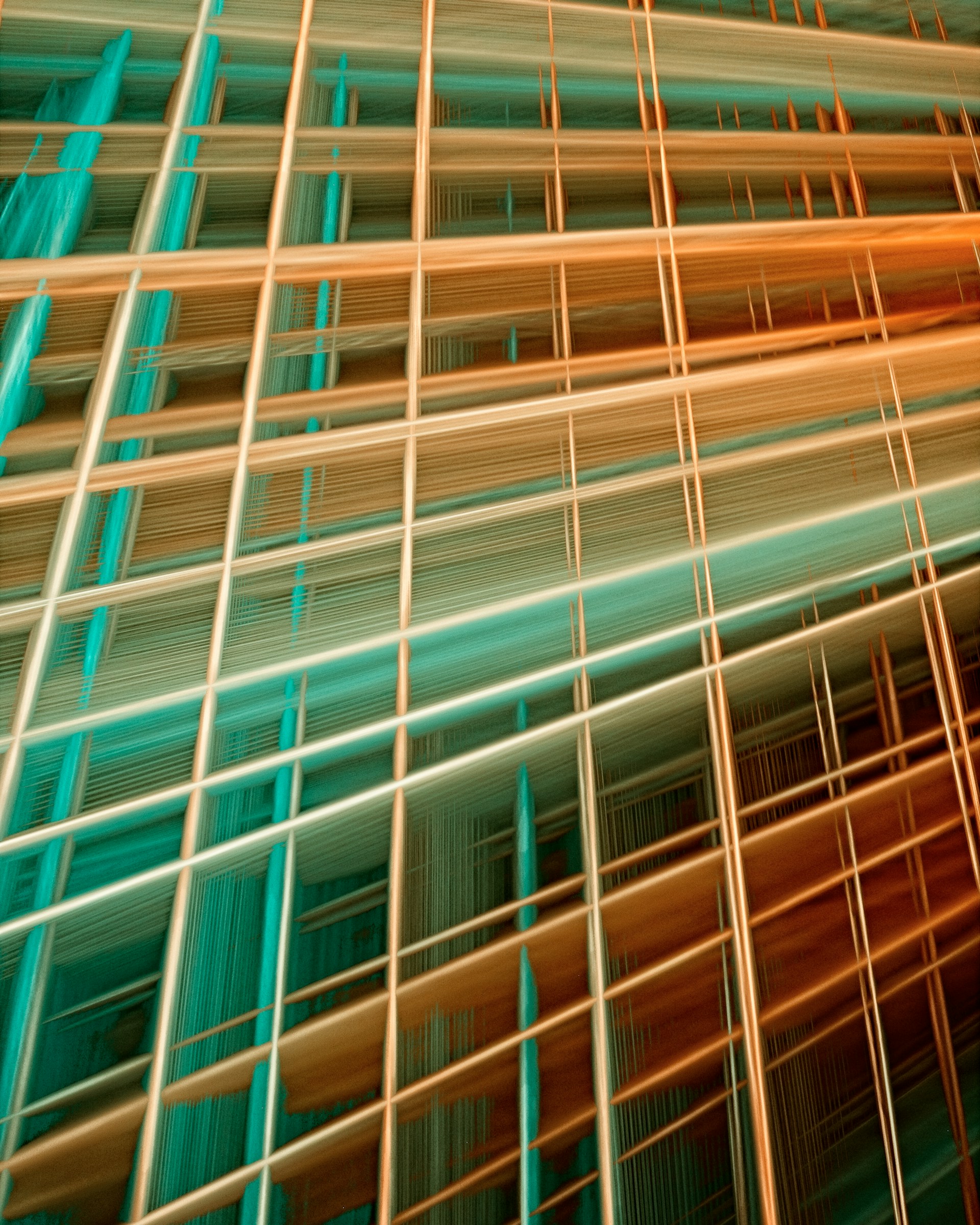

To demonstrate the Engine's power, she outlines a step-by-step sequence of operations for it to calculate a complex series known as the Bernoulli numbers. This detailed, intricate process is now widely considered to be the first complete computer program ever written.⁴ But more important than the code itself was the metaphor she used to explain its potential. The Analytical Engine's punch cards were borrowed directly from the Jacquard loom, a revolutionary machine that used cards with holes to dictate the intricate patterns woven into fabric. Lovelace seized on this. She saw that just as the loom could weave "flowers and leaves," the Analytical Engine could be made to "weave algebraic patterns."⁵

This was the profound, conceptual leap. She understood that the numbers the machine processed could represent anything: musical notes, letters, logical symbols. The Engine wasn't just a number-cruncher; it was a symbol-manipulator. This insight led to her most startling prophecy, a vision of generative computing written down more than a century before its time:

"The Analytical Engine," she wrote, "...might act upon other things besides number... Supposing, for instance, that the fundamental relations of pitched sounds in the science of harmony and of musical composition were susceptible of such expression and adaptations, the engine might compose elaborate and scientific pieces of music of any degree of complexity or extent."⁵

A machine that could create. Not just calculate, but compose. This was the soul in the machine—an idea born from the daughter of a poet.

But her grand vision, her eloquent description of a digital future, was all written for a machine that remained a ghost. It existed only in thousands of pages of Babbage's designs and a few tantalizing, handcrafted pieces of brass and steel. Her software was written for hardware that was never fully built. Her prophecy was tethered to the ambitious, unrealized, and ultimately heartbreaking dream of its brilliant inventor. To understand why the computer age didn't begin right there, in Victorian England, you must first understand the man who drew the blueprint—and the world that wasn't yet ready for his creation.

Citations:

¹ A description of Lord Byron famously attributed to Lady Caroline Lamb. Learn more about the source of this famous quote.

² Lovelace, Ada. Letter to her mother, c. 1841. Quoted in "Ada, the Enchantress of Numbers: A Selection from the Letters of Lord Byron's Daughter and her Description of the First Computer" by Betty A. Toole. This book is an essential collection of her personal letters and can be found at most major booksellers or your local library. Find it on Amazon.

³ Hyman, Anthony. Charles Babbage: Pioneer of the Computer. Princeton University Press, 1982. A foundational biography on Babbage and his work. Available for purchase or at your library.

⁴ Isaacson, Walter. The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution. Simon & Schuster, 2014. A comprehensive modern history of the digital age. Find it at booksellers everywhere.

⁵ Lovelace, Ada. "Notes on the Sketch of The Analytical Engine Invented by Charles Babbage by L.F. Menabrea." 1843. The full text of her groundbreaking notes is available to read online.

.png)

.jpg)

_School_-_Charles_Babbage_(1792%E2%80%931871)_-_814168_-_National_Trust.jpg)