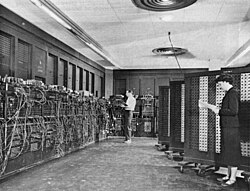

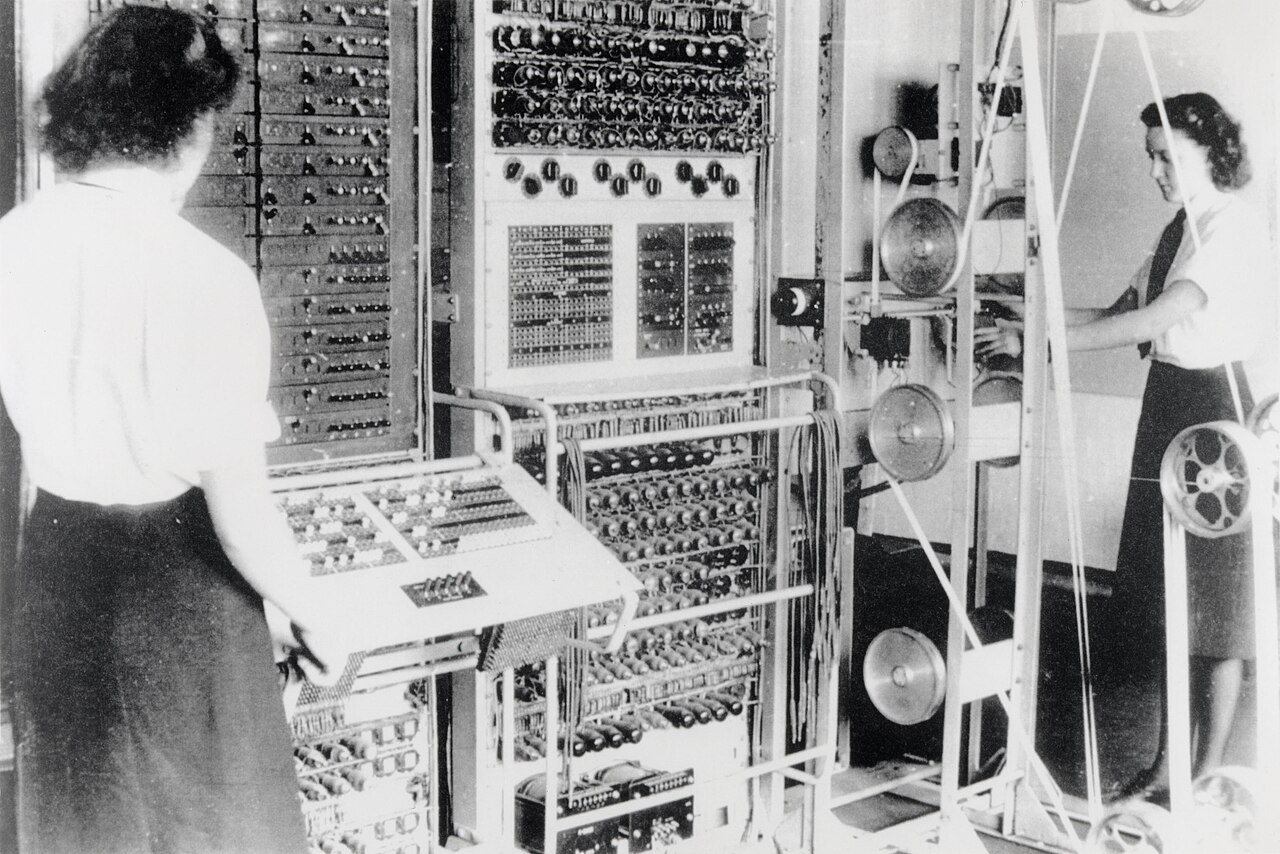

The declaration had been made. In the quiet halls of Dartmouth, a generation of scientists had set their sights on the grandest prize of all: replicating the miracle of the human mind. Their early successes, like the Logic Theororist, were stunning. They proved that a machine could, in fact, reason. But this brilliant new software was being born into a world of primitive, warring hardware tribes. The quest for a universal mind was being crippled by the lack of a universal body.

The world of computing in the late 1950s and early 1960s was a chaotic, disconnected wilderness. It was a digital "Tower of Babel." A program written for one machine was gibberish to another. Even within the same company, different models were like alien species, unable to communicate. For the AI pioneers, this meant their elegant logical proofs were trapped on whichever specific machine they had been written for. To move forward, they had to constantly reinvent the wheel. It was an innovator's nightmare.¹

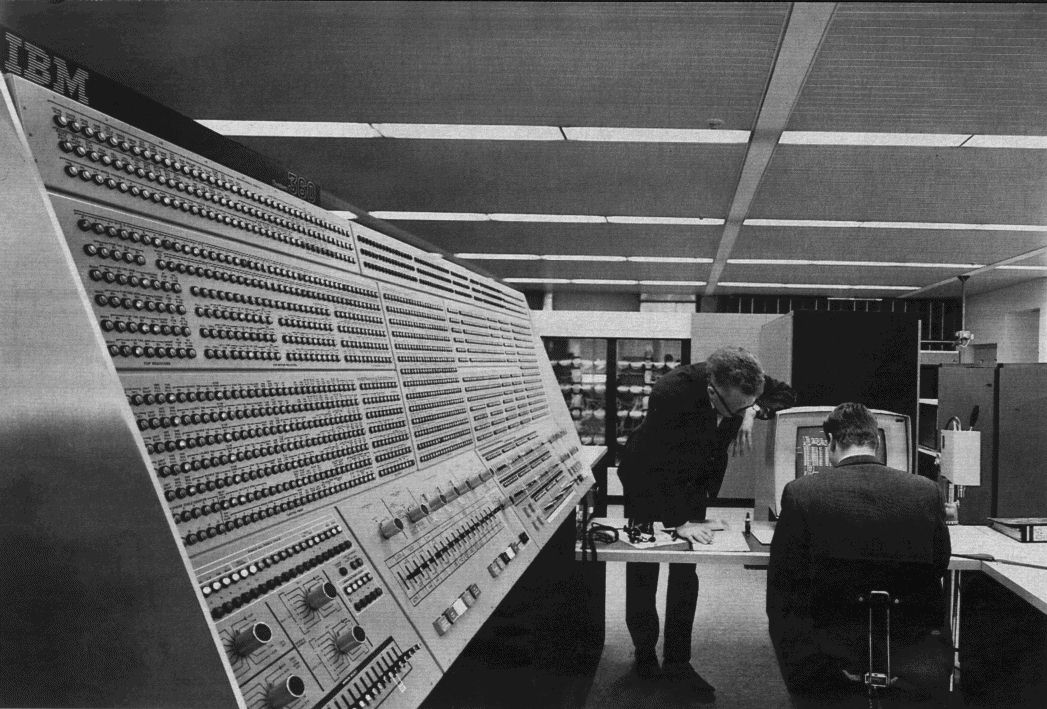

Nowhere was this problem more acute than at International Business Machines, the undisputed king of the computing industry. IBM was dominant, but its own house was a mess of incompatible product lines. Seeing this chaos as a fundamental barrier to progress, the company's new leader, Thomas Watson Jr., made a decision that is still breathtaking in its audacity. He decided to bet the entire company on a single, radical idea. He would scrap all of IBM's existing, profitable computer lines and replace them with one unified family of machines.²

He called it the System/360. It was a $5 billion gamble—more than the Manhattan Project that built the atomic bomb.

The idea at the heart of System/360 was a profound leap of abstraction, a direct descendant of Turing's universal machine. The engineers at IBM would separate the machine's architecture—its logical structure, the set of instructions it understood—from its implementation, the physical hardware that carried out those instructions. They would design a single architecture that could be built in a whole range of sizes and prices. The magic was that any program written for any machine in the System/360 family would run on any other machine in the family.³

This was the birth of software compatibility. It was the moment software became unstuck from hardware. For the first time, a customer—whether a business, a university, or an AI lab—could develop software on one machine knowing it could run on a bigger, faster machine in the future. The System/360 created a stable, predictable platform in a world of chaos.

Its success was colossal. It didn't just save IBM; it created the modern IT industry. It established a common standard, a lingua franca for the machine world. And in doing so, it gave the ambitious dreams born at the Dartmouth workshop a solid ground to stand on. The top-down, logical approach of Symbolic AI now had a top-down, logical hardware platform to match. The mind of the machine finally had a rational, standardized body.

But this very success, this clean, logical order, hinted at a deeper problem. The symbolic approach was brilliant at tasks that could be broken down into rules, like proving theorems or playing chess. But what about the things we do without thinking? Recognizing a face in a crowd, understanding a spoken word, learning from experience? These were tasks that resisted neat, logical formulas. For this kind of intelligence, a different approach would be needed—one inspired not by the pristine rules of logic, but by the messy, tangled, and mysterious wiring of the brain itself.

Citations:

¹ Pugh, Emerson W., Lyle R. Johnson, and John H. Palmer. IBM's 360 and Early 370 Systems. MIT Press, 1991. The definitive technical and business history of the project. Available for purchase or at university libraries.

² Watson Jr., Thomas J., and Peter Petre. Father, Son & Co.: My Life at IBM and Beyond. Bantam, 2000. Watson's autobiography, which provides a firsthand account of the monumental risks and decisions behind the System/360 project. Available at major booksellers.

³ Brooks Jr., Frederick P. "The Design of the System/360." Published in Annals of the History of Computing, IEEE, 2010. A look back at the architectural principles by one of the lead designers, the man who also wrote the legendary book on software engineering, The Mythical Man-Month. The paper can be accessed through the IEEE Xplore digital library.

.png)

.jpg)

_School_-_Charles_Babbage_(1792%E2%80%931871)_-_814168_-_National_Trust.jpg)