Alan Turing, the Cambridge logician who had imagined a universal machine on an infinite paper tape, had arrived at the front line of a new kind of war. But this front line wasn't a muddy trench or a blasted shoreline. It was a rambling Victorian estate in the heart of the English countryside, a place of sprawling lawns and quiet lakes known only by its code name: Station X. This was Bletchley Park. And it was here that the abstract ghost of the thinking machine would finally be given a body of wire and steel, not for the sake of science, but for the sake of survival.

The problem facing the Allies was a nightmare of industrial-scale logic. The German Enigma machine was a marvel of electromechanical encryption. With its series of rotating scramblers and its plugboard, it could encode a message in one of 159 quintillion possible ways.¹ Every single day, the settings were changed, resetting the cryptographic puzzle to zero. For the U-boat wolfpacks hunting Allied convoys in the Atlantic, Enigma was the key to their deadly coordination. For the men and women at Bletchley Park, breaking it was a daily race against a clock measured in ships sunk and lives lost.

Human intelligence alone couldn't beat the machine. There were simply too many possibilities to check by hand. But what the codebreakers realized was that they didn't have to fight the machine on its own terms. They could use a crucial human flaw: laziness. German operators often used predictable phrases or call signs in their messages—a weather report, a standard greeting. This predictable text, what the codebreakers called a "crib," was the chink in the armor. It gave them a tiny piece of the original message to work with.

The challenge was to find the one Enigma setting, out of millions, where that crib would match the encrypted text. This was still a monumental task. And this is where Alan Turing’s abstract genius met the brutal reality of war. Working with his brilliant colleague Gordon Welchman, Turing designed a machine to automate that search. It was not a universal machine; it was a highly specialized weapon. They called it the Bombe.²

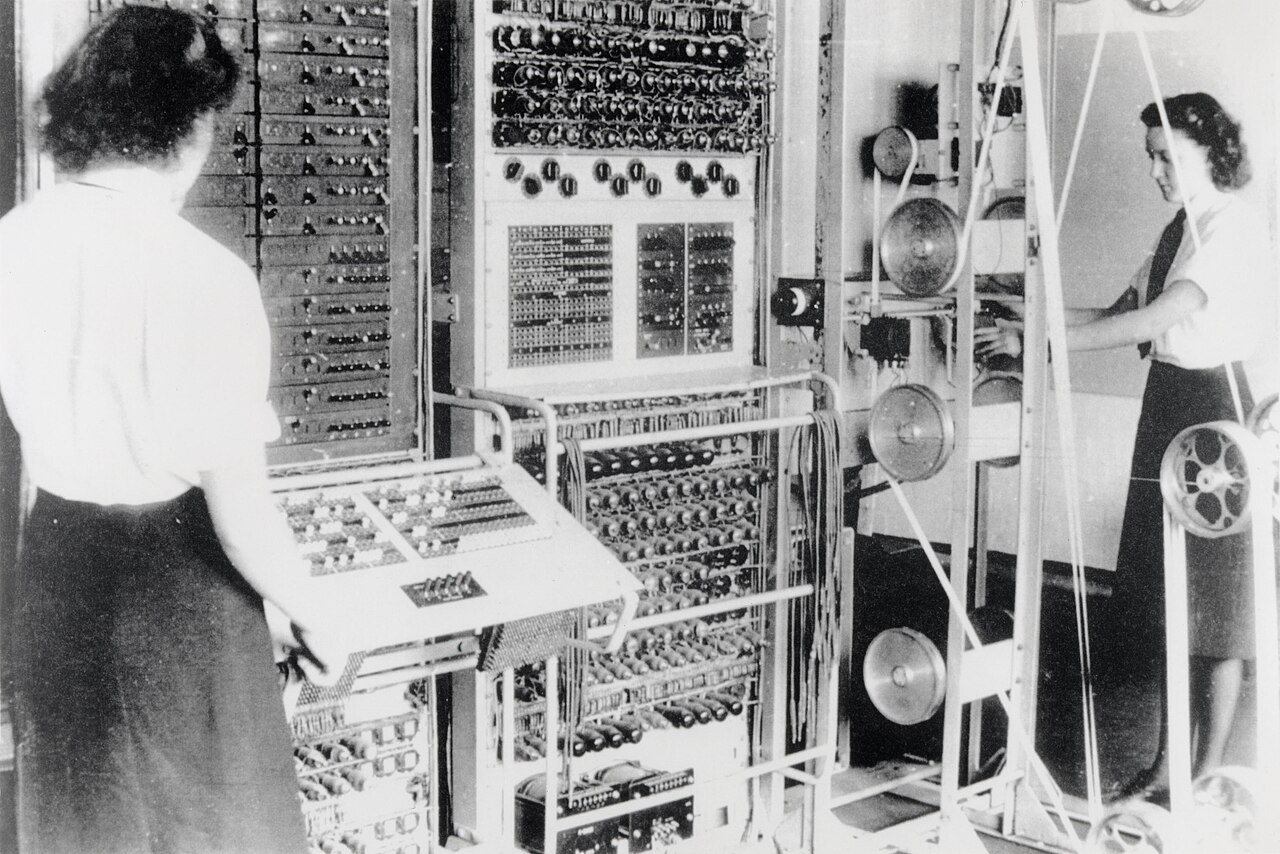

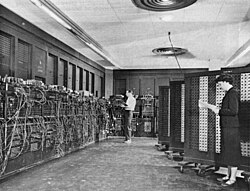

The Bombe was Babbage’s dream reborn in the crucible of war. It was a colossal cabinet of whirring dials and clicking relays, a multi-ton electromechanical beast that simulated the logic of dozens of Enigma machines working in concert. The codebreakers would feed it a suspected crib, and the Bombe would churn through every possible rotor setting at high speed, looking for a logical contradiction. When it found a setting that didn't result in a contradiction, it would stop, signaling a potential solution. It wasn't "thinking" in the way Turing had mused about in his papers. It was a brute-force logic engine, an automated process of elimination on a scale never before seen.

But the machine was only one part of the story. The true genius of Bletchley Park was the human network that surrounded it, an incredible orchestra of talent that Babbage could only have dreamed of. Here were not just mathematicians like Turing, but linguists, chess grandmasters, and even the winners of a crossword puzzle competition, all chosen for their ability to see patterns where others saw only noise.³ It was this diverse collection of minds—thousands of them, the majority of whom were women who operated the machines and managed the immense flow of information—that made the system work. They were the ones who found the cribs, who interpreted the results, and who wove the fragments of decrypted messages into a coherent picture of the enemy’s actions.

The impact was staggering. Historians estimate that the intelligence flowing from Bletchley Park—codenamed "Ultra"—shortened the war by at least two years, saving countless lives.⁴ It was a secret victory, a war won by logic and information, a triumph of intelligence in every sense of the word.

But as the war ended, the secret was buried. The Bombes were dismantled, the documents burned. The heroes of Bletchley Park were sworn to a silence they would maintain for decades. They had proven, beyond any doubt, the power of high-speed computation. They had built a machine that could perform logical tasks at a speed that dwarfed the human mind. The world, however, didn't know it yet.

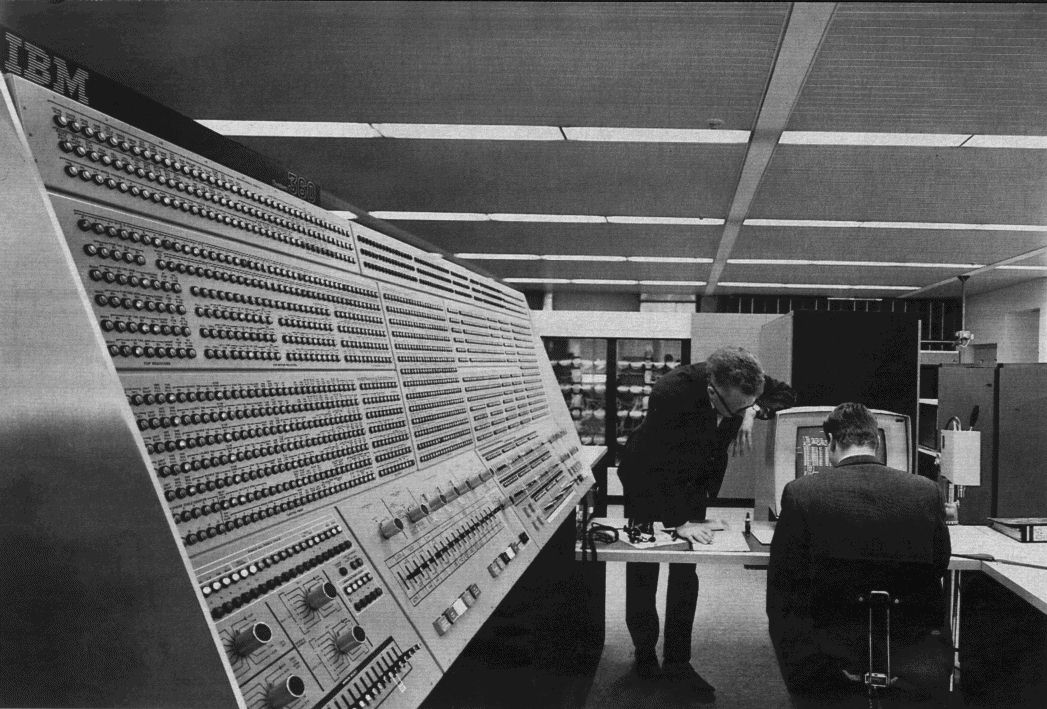

The specialized, secret machines of Bletchley had served their purpose. But the question that had driven Babbage and Turing was no longer a secret. Could you build a machine that wasn't a specialist? A truly universal, programmable computer that could be put to any task, not just for war, but for science, for business, for everything? The answer would come not from a secret country estate, but from a university in America, in a sprawling, public spectacle of flashing lights and raw power that would finally, officially, kickstart the computer age.

Citations:

¹ Bletchley Park. "The Enigma Machine." A detailed explanation of the machine's complexity and the challenge it posed. Available to read at the official Bletchley Park website.

² Hodges, Andrew. Alan Turing: The Enigma. Princeton University Press, 2012. The definitive biography of Turing, with extensive detail on his work on the Bombe. Available at major booksellers.

³ McKay, Sinclair. The Secret Lives of Codebreakers: The Men and Women Who Cracked the Enigma Code at Bletchley Park. Plume, 2012. An accessible history focusing on the diverse people who worked at Bletchley. Available for purchase or at your library.

⁴ Hinsley, F. H., et al. British Intelligence in the Second World War. Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1979-1990. The official history, which concluded that the Ultra intelligence was a decisive factor in the Allied victory. [This multi-volume work is a major academic source, available at university and national libraries.]

.png)

.jpg)

_School_-_Charles_Babbage_(1792%E2%80%931871)_-_814168_-_National_Trust.jpg)