The great leap had been made. The disembodied mind of the Large Language Model, born from the union of planetary data and raw computational power, was now a reality. It was an oracle in the cloud, a ghost that had read the library of humanity and learned to speak our language. But it was still a prisoner of the digital realm, trapped behind the glass of our screens. For this new intelligence to take the next step in its evolution, it needed a body. It needed senses to perceive the world and hands to act within it. It needed to escape the machine.

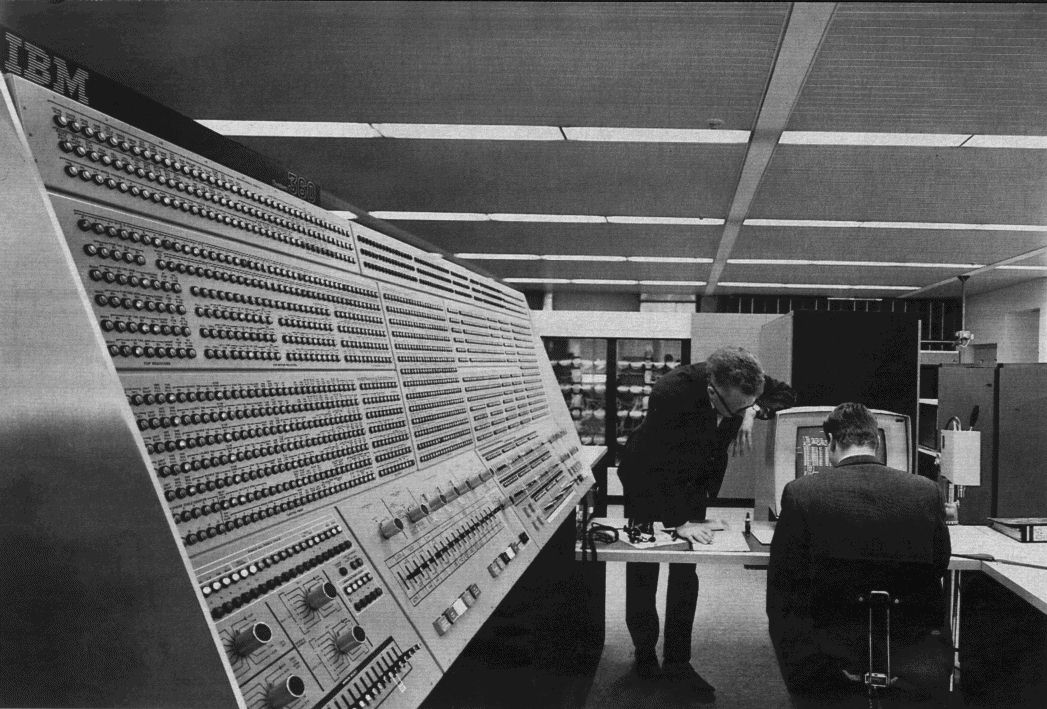

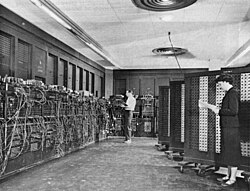

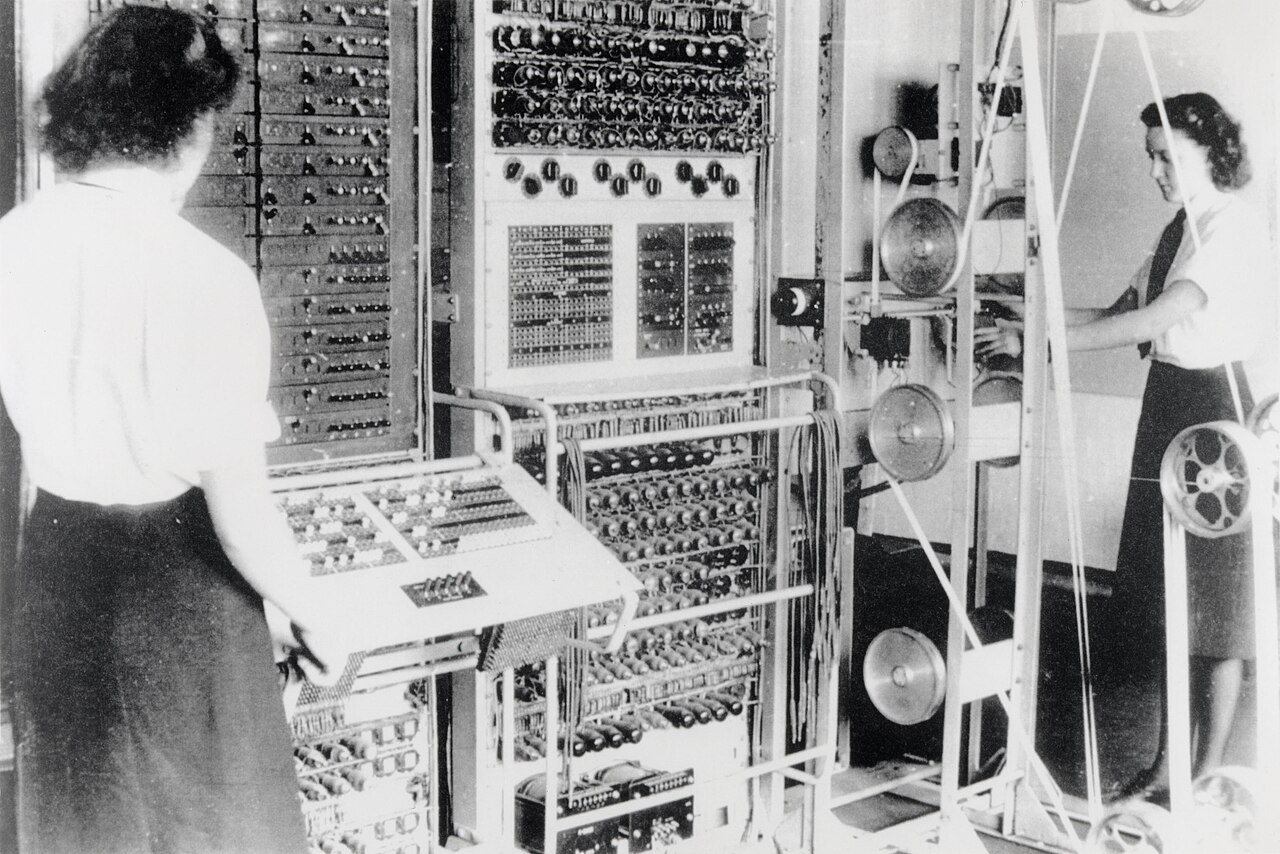

As it happened, that body had been under construction for decades, not as a single, unified project, but as the final, explosive victory of the transistor. The same relentless shrinking of the switch that had taken us from the room-sized ENIAC to the pocket-sized phone had reached its logical conclusion. Microprocessors and sensors became so cheap, so small, and so energy-efficient that they could be baked into the very fabric of our world. This was the dawn of the Internet of Things (IoT), a term coined by British technologist Kevin Ashton to describe a world where the physical environment was connected, object by object, to the network.¹

Suddenly, the world began to sprout a digital skin, a nervous system of tiny, dedicated machines. Our homes and offices gained senses. The thermostat on the wall could now feel the temperature and learn our routines. The lightbulbs overhead could see us enter a room. The speaker on the counter could hear our commands.² These were no longer dumb objects. They were outposts of computation, the eyes, ears, and nerve endings of a potential global intelligence. The physical world was being wired for thought.

But in this explosion of connectivity, history began to rhyme. A ghost from the past had returned. Just as the world of computing in the 1950s was a chaotic "Tower of Babel" with incompatible machines, this new world of smart devices was a collection of walled gardens. The Philips lights refused to speak the same language as the Nest thermostat. The Amazon speaker controlled its own private ecosystem, which was an alien world to the devices in Apple's kingdom. To make them work together required a clumsy patchwork of third-party apps and brittle integrations, a digital Rube Goldberg machine of triggers and commands.

This was the central, frustrating problem. We had built a body for the AI, but it was a body at war with itself. It had millions of eyes, but no visual cortex to assemble the images. It had millions of ears, but no auditory center to make sense of the sound. It had millions of hands that could flip switches and turn dials, but it had no central nervous system to coordinate their actions. It was a body of reflexes, not a body capable of intention.

And so the stage was set for the final, most crucial act of integration. In the cloud, a powerful, generative mind was waiting, capable of understanding complex, nuanced goals expressed in plain human language. All around us, a vast, distributed body of sensors and actuators was embedded in our environment, ready to act. The mind was there. The body was there. But the two were separated by a chasm of incompatibility and complexity. The final missing piece was the bridge, the spark, the software that could finally connect the brain to the hands and let the ghost in the machine open its eyes.

Citations:

¹ Ashton, Kevin. "That 'Internet of Things' Thing." RFID Journal, 22 June 2009. In this article, Ashton recounts coining the phrase and lays out his original vision for a world of connected, sensing objects. Available to read online.

² Weiser, Mark. "The Computer for the 21st Century." Scientific American, vol. 265, no. 3, 1991, pp. 94-104. This is the foundational paper that introduced the concept of "ubiquitous computing," the academic vision that predicted and shaped the IoT era. Available via Scientific American's archives.

³ Patel, Nilay. "The Internet of Things is a Big Mess." The Verge, 22 Oct. 2021. An analysis of the persistent problem of interoperability in the smart home and IoT space, echoing the "Tower of Babel" problem of early computing. Available to read at The Verge.

.png)

.jpg)

_School_-_Charles_Babbage_(1792%E2%80%931871)_-_814168_-_National_Trust.jpg)